Python is going through a huge modernisation kick in recent years with things like PEP 484 Type Hints, performance improvements coming in 3.11 and now being able to run on web assembly, moving away from the hangover of python 2 and fully embracing the new style of “modern” python 3.

The python sphere is full of posts, packages and repos claiming to use or take advantage of “modern python”

So you may be asking… what exactly do people mean when they say “modern python”? What follows is a list of what I consider to the most essential components of “modern python” and by the end hopefully you’ll want to make sure you’re doing “modern python” too!

Type Hints

Let’s start with my favourite bit… type hints!

PEP 484 introduced type hints to the language. A system where the programmer can provide the types of function arguments, variables, class variables etc. almost like you would in a statically typed language. You know, the things you see that look like this…

def count(things: list[str]) -> int:

"""

Counts the number of things in a list of things.

"""

return len(things)

PEP 484 itself is pretty old now, type hints have been around a while. However, what I think makes them part of this new “modern python” is the fact that libraries have been jumping on them and using them in novel ways and that they are now so widely used that they are massively improving how it feels to write python!

Type hints are exactly that… a hint. They do absolutely nothing at runtime. But some libraries like FastAPI, Pydantic and others have been using these annotations at runtime to serialise, deserialise and validate data.

You can also use type checkers such as mypy to effectively act as a sort of “compiler frontend” for python that will parse all these hints and statically determine if your code is type safe. In fact with things like mypyc, you can even compile your python code to C using these type annotations, mypy has been compiled with mypyc as has black, resulting in 2 - 4x speed improvements!

And when it comes to writing python, they make it so. much. better.

It’s gotten to the point now where I can’t really even write non-typed python anymore and I genuinely view non-typed python as a bit of a code smell.

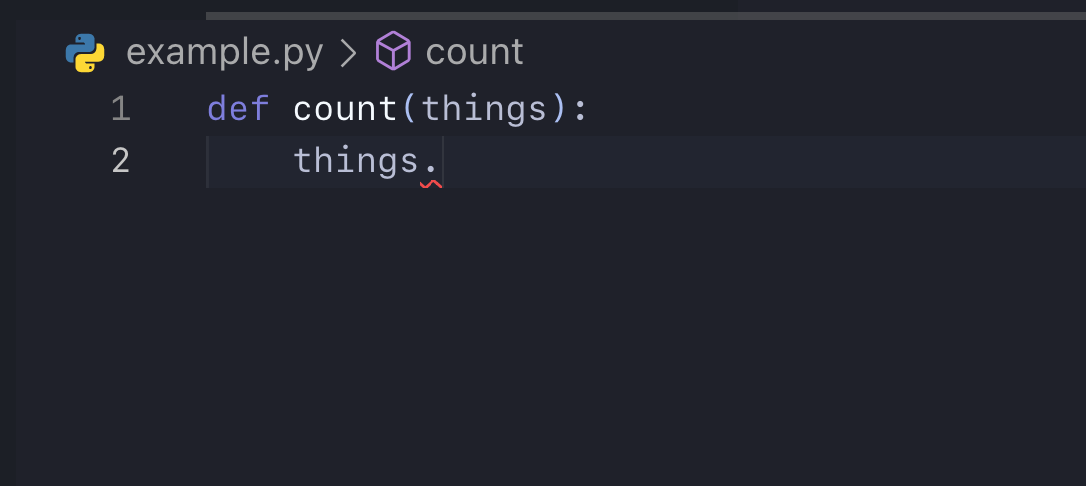

Consider the following example from VSCode:

See how it gives you absolutely no help whatsoever? What is a thing? The argument things seems to suggest some collection of type thing. Is it a list? a set? a dictionary? Who knows!

And if we try and call a method on it, we need to know what it is and then google the methods on that type! Madness, it’s 2022.

Some python purists will now be yelling at the screen “But it’s a dynamic language!! The whole point is the argument CAN be anything!”

And yes, they have a point, python is and will always be a dynamically typed language. The types of everything are evaluated at runtime and the flexibility that offers has made python as popular and as powerful as it is.

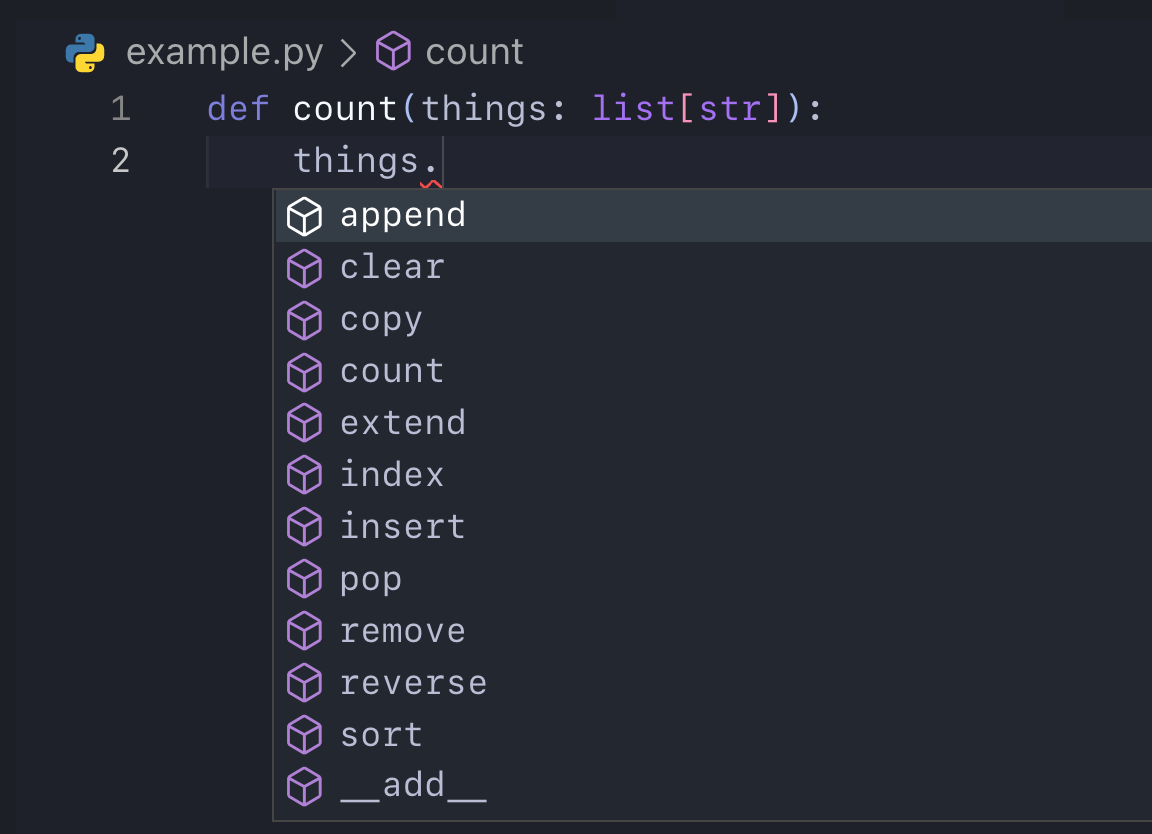

But why wouldn’t you want this:

Just like that all is well with the world again, we know exactly that our things is a list of strings and we have instant access to all the methods that can be applied to a list.

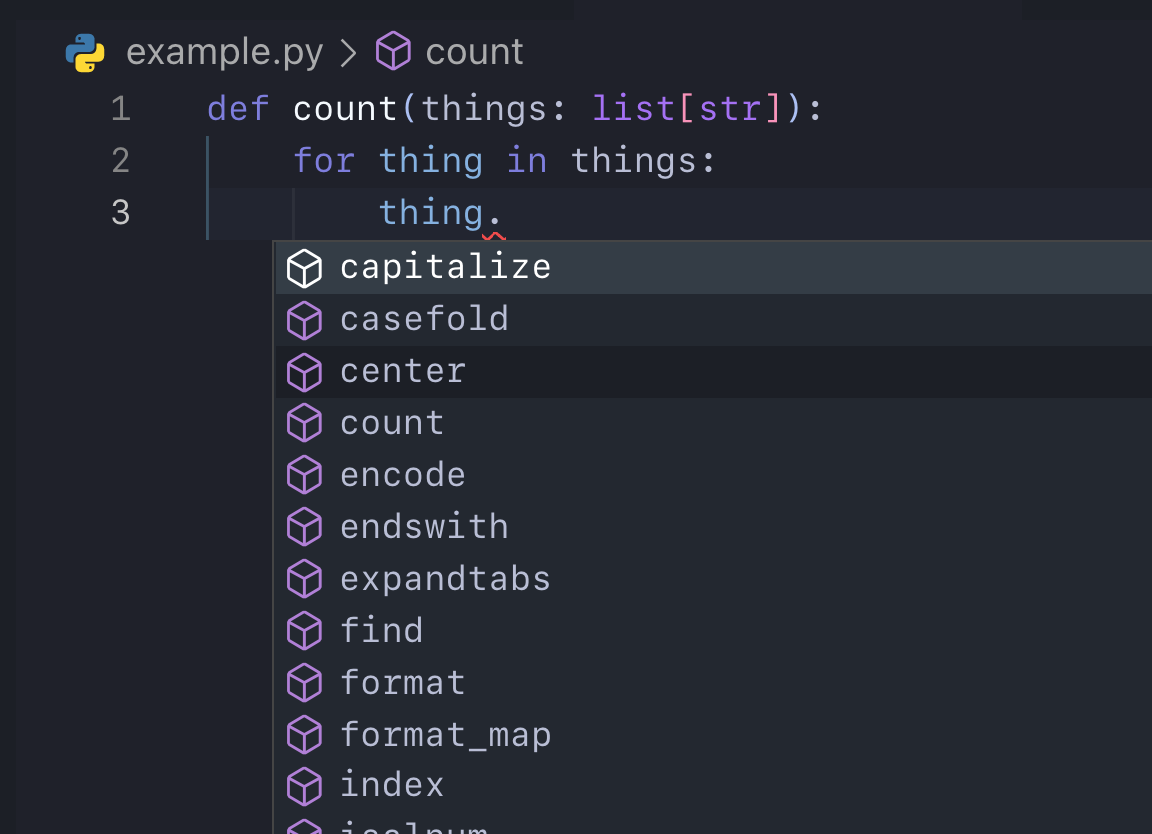

Even better than that, because its a list of strings, we get even more help:

Look! It knows the things inside our list are strings!

Alright, this was a very simple example and typing does have its sharp edges. But I’ve used it in every one of my projects large and small and in my opinion, there is very little excuse for non-typed python these days, especially if you’re a library author; if a library doesn’t have a typed public API I’m not even going near it! I’ve caught many bugs early and the editor support has helped me develop things faster and with more confidence. It’s a no brainer for me 🧠

Packaging Standards

The old meme is that “python packaging is a mess”, “pip sucks” blah blah. Ignoring the fact that this isn’t exactly well-meaning criticism, it’s definitely not correct anymore!

The python packaging authority (pypa) has been on an absolute mission in the last few years to establish some really robust specs and standards around packaging.

Things like PEP 517, PEP 518, PEP 621 are all leading away from the old setup.py that could run basically any code it saw fit to install itself to the new pyproject.toml and setup.cfg declarative install config that runs in a completely isolated environment to install your package.

And because we now have formal specifications and standards on how packaging should work, it’s enabled third party tools like poetry and flit to start providing alternative options for package management, all because of PEP 517 and PEP 518!

PEP 621 defines a formal standard of what should go in a pyproject.toml so the community can standardise around it.

And there are loads more examples like this e.g. pip’s new dependency resolver.

All this is to say that these new packaging standards are already well adopted and the packaging story in python will continue to get better and better.

If you want to be practicing “modern python” in a packaging context, you need to:

- Ditch the

setup.pyforsetup.cfgandpyproject.toml - Ensure you’re on the latest

pip - Get as much into the

pyproject.tomlas you can as it’s likely going to be the standard place for all python packaging info in the future - No more

python setup.py bdist_wheel, use the new build tool (python -m build)

Latest Versions

This comes as no surprise that to practice “modern python”, you need to be on a modern version of python itself.

Python 3.6 reached EOL in December 2021, which now means the oldest supported version is now 3.7. Kind of crazy to think as I’m not a veteran python developer, I’ve only been doing it for about 2 years and I started on python 3.5!

Anyone still using <3.7 should upgrade now!

The default python on my machine is the latest 3.10.2 (at time of writing), I also keep 3.9 and 3.8 on there (thanks pyenv) for testing open source stuff locally (I help maintain Nox which supports all current python versions).

But I highly recommend anyone to have, at least, 3.9 as their default python installation. Each minor version comes with bug fixes, performance improvements, features, removals, deprecations and all sorts of good stuff so why miss out!

3.8 got the walrus operator which, despite the weird overreactions and controversy, is actually quite useful:

# Isn't this nicer

if x := some_function() >= 3:

# Do something

# Than this

x = some_function()

if x >= 3:

# Do something

This really comes in handy for me when dealing with dictionaries:

items = {"apple": 4, "banana": 1, "orange": 2}

if fruit := items.get("lime"):

# Do something that requires lime to be in the dict

else:

# Lime was missing

Isn’t that nicer than:

items = {"apple": 4, "banana": 1, "orange": 2}

fruit = items.get("lime")

if not fruit:

# Handle the missing case

else:

# Lime was found

3.9 brought the nicer type hint syntax (with the __future__.annotations switch):

# Old

from typing import Optional, List

def function(item: Optional[List[str]]) -> str:

...

# New

def function(item: list[str] | None) -> str:

...

Nicer right?

And 3.10 has structural pattern matching which to be honest I haven’t played with yet because it would break my projects that have to work on other versions but it looks awesome!

def make_point_3d(pt):

match pt:

case (x, y):

return Point3d(x, y, 0)

case (x, y, z):

return Point3d(x, y, z)

case Point2d(x, y):

return Point3d(x, y, 0)

case Point3d(_, _, _):

return pt

case _:

raise TypeError("not a point we support")

You can actually match on the structure of the object not just the type or value, really impressive!

PS. My prediction for this is someone is going to write a ridiculously powerful CLI toolkit using this, imagine something like click but able to match on type, value and structure of commands, flags and arguments. As someone who loves writing CLIs, my mouth is watering at the prospect!

Async/Await

Okay here we go, some real stuff here!

Asyncio and the async/await syntax kinda blew my mind when I first saw it and tried (and failed) to use it!

However, once you get your head around it, it’s actually amazingly powerful and it’s the exact thing that takes python; an interpreted, “slow” language and turns it into an absolute rocket ship competing with statically typed, compiled languages under certain workloads.

The trick with asynchronous code is to know your problem. You need to know if your problem is:

- IO bound: The fundamental bottleneck in your program is that it has to wait for things a lot

- CPU bound: The fundamental bottleneck in your program is that it’s doing complex calculations using all your CPU power

If it’s the first one, using asynchronous code will have huge results! If it’s the second one you’re better off calling into things like numpy, using cython or spreading the work across cores with multiprocessing.

The reason for this is that IO bound code waits for things a lot. This could be things like opening and reading files or waiting for a HTTP request to return a response etc.

And normally in python when these things happen, your code just waits for the thing to happen, then carries on to the next line.

Consider the following example:

import httpx

response = httpx.get("https://waitforever.com/")

print(response.json())

Here we’re making a HTTP request, waiting for the response, and then printing it… simple stuff. However, I’m sure you’ve noticed the url: https://waitforever.com/, (even fake sites should be encrypted).

If you ran this (and if waitforever.com was real) you would never see any output, and your program would never end.

More specifically, your program would wait forever at this line:

response = httpx.get("https://waitforever.com/")

Even though it doesn’t look like it because it’s all on one line, when python parses your source code, the function call is “deeper” in the abstract syntax tree, call expressions have a higher precedence and so the function call is evaluated first. So here python is calling httpx.get and assigning whatever it returns to the variable response.

But it will never return, so your python interpreter is sat at this line, completely unable to do anything else. So if you had lots of other stuff below, it would never happen.

This was a slightly silly example because no HTTP request lasts forever (and httpx is smart enough to impose a default timeout) but it gets the point across.

This is where async/await come in. At a high level, whenever you await something, you’re saying “okay, this might take a while, feel free to go and do something else while we wait.”

So the example above would now be something like:

from typing import Any

import httpx

# We now have to wrap it in a function for async to work

async def get() -> dict[str, Any]:

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

response = await client.get("https://waitforever.com/")

return response.json()

When using asynchronous code, you have to do a bit more typing; there’s the async def and with httpx you have to create an AsyncClient but I think it’s still pretty clear.

However, what’s happening now is your python interpreter will get to this line:

response = await client.get("https://waitforever.com/")

As soon as it hits the await, it will fire off client.get in the background and immediately go off to do anything else it can do (any other async functions that have things that need to be awaited). And if all of your IO bound functions in your program are written like this, it means you are effectively never blocked waiting for IO, your code will always go and do other things (unless there isn’t anything else to do of course).

This is a game changer as most real world programs are not limited by the power of the CPU they run on, they are limited by waiting for files to be read, or network requests to return. So suddenly, with a bit of extra syntax, you’ve mutliplied the efficiency of your program.

I won’t spend too long talking about what’s going on under the hood here, the details are kind of complicated and involve callbacks, futures, generators etc. Łukasz Langa has a great video series on asyncio here for those who want more detail but effectively, when an asynchronous program starts up, it spins up an “event loop”.

This is a background loop that spins and spins on it’s own waiting for “events”, an event in our case is something calling await, the event here is to go and call whatever function we’re awaiting. Once the loop has made that call, it keeps one eye on the called function but otherwise goes back to spinning the loop, waiting for more events (and running them too if it finds them).

Once the called function is ready (the http request has returned a response), on the next lap the event loop notices it’s ready, and the function enclosing our await (the get function) is allowed to return with our response.

Then the loop goes back to spinning again. Until it’s cancelled, or the program terminates.

What this means is that all the different little IO bound bits of code can run concurrently 1. So if you had to make 10 requests to different urls and their average response time was 1 second, in normal python this would take you about 10 seconds to do (plus a bit of time for setup).

If all your calling functions were like our get above and used async/await, and you combined it with something like asyncio.gather to go and run them all together, it would take about 1 second (again, plus a bit of setup).

Sounds pretty modern to me! A lot of new python libraries and programs are using asynchronous code to offer dramatic speed improvements for IO bound tasks. FastAPI for example is ranked among compiled languages in benchmarks because it’s fully asynchronous and can handle loads of HTTP requests concurrently.

I think to really do “modern python” you have to be doing async where it’s needed.

1 Note: I said “concurrently”, not “in parallel”. They are different! I’m a big fan of Go, see Rob Pike’s concurrency is not parallelism

Black

This one is really short as I have a very authoritarian opinion on code formatting.

Just use black. Please. Just use it. No arguments, no “I don’t like the way it does XYZ”, it doesn’t matter, no one 100% agrees with the style choices of black but everyone should agree 100% in not arguing about stupid little formatting things.

Rust has rustfmt built in that everyone uses, all rust code looks the same and is therefore easier to read (although personally I think it’s too configurable, thankfully its quite common in the rust community to enforce the defaults). Go has gofmt built in that everyone uses, all go code looks the same and is therefore easier to read, and gofmt is not configurable at all! Brilliant!!

IMO python should have black built in and everyone should use it, all python code everywhere in the world should be formatted the same way. If I had my way it would be a runtime error for code not to be formatted with black 💥

If you don’t current use it, here’s what I recommend:

- Use it

- Use isort too with the

--profile blackoption - Don’t configure isort to do anything other than the black profile

- Have them both run on save

- Have them both run in some sort of local automation

- Have them both run on CI so no code gets merged unless it’s been blacked

- While we’re at it, use flake8 too. And fix everything it tells you to, your contributors will thank you.

Testing

Let’s be clear, testing has been around forever so why am I including it in this list of “modern python” practices?

Well broken code isn’t very modern. And the only reliable way to determine if your code is broken is testing.

My opinion on testing is almost as authoritarian as my opinion on code formatting. I am a huge testing evangelist, code without tests is a huge smell and a huge red flag.

I see it a lot on the programming subreddits and elsewhere, someone posts their project and it looks good, but it has no tests. I’m sorry, instant no from me, I’m never using it.

I’m not saying absolutely every line of code you write must be tested and you must hit 100% coverage etc etc. If you have a little script that you run once or twice a month, that doesn’t need tests.

But if you’re writing programs, that other people might use, and might even rely on… then you should absolutely have solid test coverage with good, powerful, well-written tests.

What do I mean by a good test?

A Bad Test

Let’s say we have a Person class (by the way, you should always write a __repr__ for your classes) and let’s assume our Person

has loads of methods that do things later on that I haven’t defined here like save them to a database, assign them to a new job, stuff like that,

maybe you’re writing some sort of HR software, it doesn’t really matter.

The point is we have an object we’ve created and some behaviour we have defined on it that we’d like to test.

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int) -> None:

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"Person(name={self.name!r}, age={self.age!r})"

This is a bad test:

def test_person_initialises():

p = Person(name="Dave", age=42)

assert p.name == "Dave

assert p.age == 42

Why is it bad? It’s not testing your code at all, it’s testing that python correctly assigns attributes to classes.

You don’t need to test that, believe me. There are probably thousands of tests in the python code base that verify this.

This is the sort of test you end up with if you aim for “100% test coverage”, and yes this bit of code will be “covered”, but this test is meaningless. And

not only that, it’s a burden. If you refactor your Person class to have a new attribute, you need to change the test or it’ll break.

A Good Test

To give an example of a better test, we have to flesh out the Person class a bit more. Let’s say we want a method to add this person to

the employee manifest at some company.

class Person:

# init, repr, blah blah

...

def add_to_manifest(self, manifest: Manifest) -> None:

"""

Adds the current `Person` to the employee `manifest`.

The add is idempotent, if the person already exists in the

manifest, this becomes a no op.

"""

if not manifest.contains(self):

manifest.add(self)

By the way, note how we’ve passed in the Manifest as an argument. This is called “dependency injection” and makes testing this method really easy

because we could just pass it in a fake Manifest for just that test. Without this, add_to_manifest might have to hit an API to get the Manifest object

which would be difficult to test as we’d have to fake a http response. Knowing these little tricks is a key part in writing testable, maintainable code 👌🏻.

So we’re assuming here that our Manifest object has two methods defined on it:

containswhich has the following signature:def contains(self, person: Person) -> booladdwhich has the following signature:def add(self, person: Person) -> None

So we need to verify that when we call add_to_manifest, everything happens as we expect it to. On to the test:

# It may seem long, but always use descriptive test names

def test_add_to_manifest_correctly_adds_a_person_to_manifest():

manifest = Manifest() # Initialise an empty manifest

person = Person(name="Dave", age=42)

person.add_to_manifest(manifest=manifest)

assert manifest.contains(person)

So if our code works, this will now pass. We’ve correctly added a person to the manifest and provided that the Manifest class and all it’s methods

are tested, we can be confident that our system works as intended.

However, we’re missing something. We’ve only tested the happy path, what if the person is already in the manifest, we need to make sure they aren’t added twice.

def test_add_to_manifest_is_idempotent():

manifest = Manifest()

person = Person(name="Dave", age=42)

same_person = Person(name="Dave", age=42)

person.add_to_manifest(manifest=manifest)

same_person.add_to_manifest(manifest=manifest)

assert manifest.contains(person)

assert len(manifest.people) == 1

Depending on the application, it might make sense to raise an Exception here, we’ve just made it idempotent instead so it doesn’t matter if you call it with the same person. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages and it’s really down to what your software needs as to which one you pick.

CI & Automation

Okay so let’s assume we have a project and we have some good tests to go with it. How do we run these tests? Do we just do pytest, do we have a Makefile? Are we relying on contributors to run their own tests before raising a PR?

The answer to all those (as I’m sure you’ve guessed) is No!

IMO any moderately sized python project should do the following:

- Run the tests often (on any change or PR)

- Run linting and style checks on any change or PR

- Enforce these things via CI such that

mainis always passing - Provide the users with some easy way of running “CI” locally

I think the first 3 are pretty obvious and there are plenty of CI options these days:

And probably loads more!

There’s way more to talk about in CI than I can fit in this post so I’m going to focus on the last of my 4 points: “Provide the users with some easy way of running CI locally”

There are a few requirements that I think are key in this category:

- It should be well documented what the users should do

- It should be a very simple command

- It should be reproducible and not flaky

- It should run an equivalent set of checks as CI does

What I use for this is Nox. It ticks all of my boxes above and unlike tools like make, it’s configuration is in python 🎉.

Let’s take a look at a simple noxfile.py

# noxfile.py

import nox

@nox.session

def test(session: nox.Session) -> None:

"""

Run the unit tests.

"""

session.install("pytest")

session.install(".") # Install our project

session.run("pytest")

There’s a few things going on here:

- We’re declaring this thing called a

sessionwhich we nametest - We give it a little docstring

- It seems to install stuff?

- And then it runs

pytest

So lets break it down.

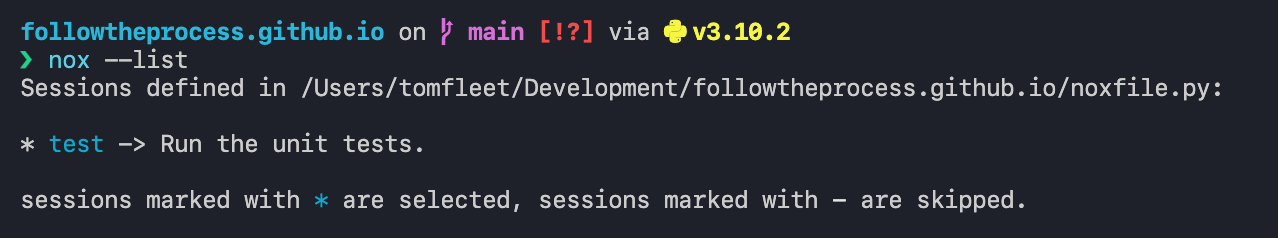

In Nox, a session is a little unit of work you need to do like run the tests, format the code, run linting etc etc. Sessions look mostly like normal python functions and the docstring is used to show the help for the task at the command line! For example our snippet above will get you this:

What Nox does here is when you call session.install, it first creates a python virtual environment in $CWD/.nox/test and then effectively shells out to pip to install whatever you’ve asked for. This means that every Nox session like this runs in it’s own python virtual environment by default, which means more or less complete isolation from the rest of your project, which is great!

All the commands after this step are all run using the virtual environment’s python interpreter too!

This is massively simplified view on what’s actually going on and there’s loads of configuration and customisation you can do, including parametrizing your test across loads of python versions which is Nox’s killer feature IMO! Check out the Nox docs for more info.

Wrap Up

And that about finishes it, I could go on forever about this sort of stuff (but I won’t). The above is by no means an exhaustive list but it’s a good start 👍🏻