The Pattern#

You may have seen this sort of thing in Go code before:

At the top, a constant block using iota

// Most often a uint, sometimes given a new type

type Something uint

const (

FirstThing Something = 1 << iota

SecondThing

ThirdThing

// ... more

)

Then it gets used somewhere, like in this struct for example

type someStruct struct {

// ... other stuff here

flags Something // What?

}

And then further down you see something like:

if s.flags&ThirdThing {

// Do something...

}

In fact, this turns up all over the place in the Go standard library. Here’s an example from text/tabwriter:

// Formatting can be controlled with these flags.

const (

// Ignore html tags and treat entities (starting with '&'

// and ending in ';') as single characters (width = 1).

FilterHTML uint = 1 << iota

// Strip Escape characters bracketing escaped text segments

// instead of passing them through unchanged with the text.

StripEscape

// Force right-alignment of cell content.

// Default is left-alignment.

AlignRight

// Handle empty columns as if they were not present in

// the input in the first place.

DiscardEmptyColumns

// Always use tabs for indentation columns (i.e., padding of

// leading empty cells on the left) independent of padchar.

TabIndent

// Print a vertical bar ('|') between columns (after formatting).

// Discarded columns appear as zero-width columns ("||").

Debug

)

// ...snip

func (b *Writer) Init(output io.Writer, minwidth, tabwidth, padding int, padchar byte, flags uint) *Writer {

// ...snip

if padchar == '\t' {

// tab padding enforces left-alignment

flags &^= AlignRight

}

b.flags = flags

b.reset()

return b

}

And in io/fs…

// A FileMode represents a file's mode and permission bits.

// The bits have the same definition on all systems, so that

// information about files can be moved from one system

// to another portably. Not all bits apply to all systems.

// The only required bit is [ModeDir] for directories.

type FileMode uint32

// The defined file mode bits are the most significant bits of the [FileMode].

// The nine least-significant bits are the standard Unix rwxrwxrwx permissions.

// The values of these bits should be considered part of the public API and

// may be used in wire protocols or disk representations: they must not be

// changed, although new bits might be added.

const (

// The single letters are the abbreviations

// used by the String method's formatting.

ModeDir FileMode = 1 << (32 - 1 - iota) // d: is a directory

ModeAppend // a: append-only

ModeExclusive // l: exclusive use

ModeTemporary // T: temporary file; Plan 9 only

ModeSymlink // L: symbolic link

ModeDevice // D: device file

ModeNamedPipe // p: named pipe (FIFO)

ModeSocket // S: Unix domain socket

ModeSetuid // u: setuid

ModeSetgid // g: setgid

ModeCharDevice // c: Unix character device, when ModeDevice is set

ModeSticky // t: sticky

ModeIrregular // ?: non-regular file; nothing else is known about this file

// Mask for the type bits. For regular files, none will be set.

ModeType = ModeDir | ModeSymlink | ModeNamedPipe | ModeSocket | ModeDevice | ModeCharDevice | ModeIrregular

ModePerm FileMode = 0777 // Unix permission bits

)

// IsDir reports whether m describes a directory.

// That is, it tests for the [ModeDir] bit being set in m.

func (m FileMode) IsDir() bool {

return m&ModeDir != 0

}

And you may be thinking…

What do integers have to do with flags or configuration? How is

iotainvolved? Why are we using bitshifting (<<)? And what do all these&^=operators do?

If you are, this post is for you!

Powers of 2#

In order to understand this pattern, we need to remember that computers speak binary. Everything is ultimately just ones and zeros under the hood:

1is just0001in binary2is just00103->00114->0100

And so on… There are plenty of great explanations of binary on the internet so I won’t do it to death here, hopefully you’re following the basics!

Observe that powers of 2 (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 etc.) have only a single 1 bit with the rest being 0, but the location of this bit moves one slot to the left every time you increase the power of 2:

| Decimal | Binary |

|---|---|

1 | 00000001 |

2 | 00000010 |

4 | 00000100 |

8 | 00001000 |

16 | 00010000 |

32 | 00100000 |

64 | 01000000 |

128 | 10000000 |

iota#

In Go, we can express this easily as compile time constants using iota:

package main

import "fmt"

const (

one = 1 << iota

two

four

eight

sixteen

thirtyTwo

sixtyFour

oneHundredAndTwentyEight

)

func main() {

fmt.Printf("sixteen:\t%d\t%08b\n", sixteen, sixteen)

fmt.Printf("thirtyTwo:\t%d\t%08b\n", thirtyTwo, thirtyTwo)

}

I’ve used fmt.Printf to output the number in both decimal (%d) and in binary, zero-padded to make up 8 bits (%08b)

Which outputs:

sixteen: 16 00010000

thirtyTwo: 32 00100000

iota here: https://go.dev/wiki/IotaYou can see the 1 moving (or shifting… 😏) one slot to the left. This is because iota will increment by 1 on every new constant in the block (starting from 0). And our

constant block above has 1 << iota as the initial expression.

In other words, take the value of iota and left shift 1 (00000001) by that value. Here’s a breakdown of what’s really going on in the snippet above:

| Constant | iota | Effective Expression | Value (Decimal) | Value (Binary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

one | 0 | 1 << 0 | 1 | 00000001 |

two | 1 | 1 << 1 | 2 | 00000010 |

four | 2 | 1 << 2 | 4 | 00000100 |

eight | 3 | 1 << 3 | 8 | 00001000 |

sixteen | 4 | 1 << 4 | 16 | 00010000 |

thirtyTwo | 5 | 1 << 5 | 32 | 00100000 |

sixtyFour | 6 | 1 << 6 | 64 | 01000000 |

oneHundredAndTwentyEight | 7 | 1 << 7 | 128 | 10000000 |

You can see that iota just starts at zero, and increments by 1 every time there’s a new constant in the block. On each new constant we’re left shifting 1 by that new iota

amount, again starting from zero. So one is 1 << 0, two is 1 << 1 and so on.

So we’ve actually already answered two of our questions from the top of the article!

Why is iota involved? And why are we bitshifting to the left?

Because this is is an easy way of generating integers that are powers of two, especially when combined with Go’s iota which lets us do this at compile time and give the

resulting constants helpful names. These binary integers differ only by a single bit, the position of which moves left by one slot on every power of two.

Configuration#

So how does this relate to configuration and state management? This power of two thing is cool but what do I actually use it for?

Well imagine you have a program that is configurable in some way, with toggles and switches that indicate that it should do one thing or another.

You might have a Config struct that looks a bit like this:

type Config struct {

Cache bool // Whether to cache results

Reset bool // Controls whether to reset something after each run

Debug bool // Enable debug mode

Secure bool // Whether to use a secure protocol

}

These are all meaningless in our imaginary program but you can see the pattern, lots of on/off switches represented as booleans. The code that uses this config will likely have lots of things like this:

if config.Reset {

// Do the resetting

}

if config.Secure {

// Use HTTPS

}

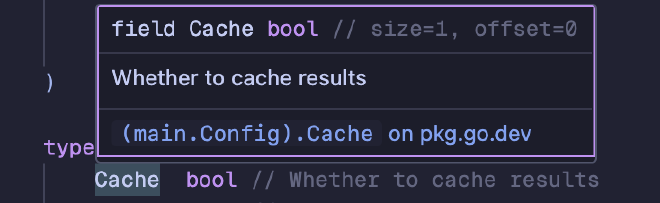

You may imagine that a bool might be implemented in computers as a single bit, 1 (on/true) or a 0 (off/false). But you’d be wrong! Hovering over the fields

of our Config struct in an editor that uses gopls reveals that a bool has a size of 1 byte (or 8 bits)

So thats 8x larger than the information it’s expressing!

And our Config struct has 4 of these, so for expressing 4 bits of information, we’re using 4 * 8 bits = 32 bits of space. Surely we can be more efficient than that? 🤔

Of course!

Recall our integer constants increasing in powers of two, and how each only has a single bit set to 1, the position of which moves to the left in every increasing power of two.

What if we named our constants differently… and gave them a type…

package main

import "fmt"

// Config holds configuration switches for our program.

type Config uint

const (

Cache Config = 1 << iota // Whether to cache results

Reset // Control whether to reset something after each run

Debug // Enable debug mode

Secure // Whether to use a secure protocol

)

func main() {

fmt.Printf("Cache:\t%d\t%08b\n", Cache, Cache)

fmt.Printf("Reset:\t%d\t%08b\n", Reset, Reset)

fmt.Printf("Debug:\t%d\t%08b\n", Debug, Debug)

fmt.Printf("Secure:\t%d\t%08b\n", Secure, Secure)

}

This outputs:

Cache: 1 00000001

Reset: 2 00000010

Debug: 4 00000100

Secure: 8 00001000

Can you tell where we’re going yet?

In this setup, it would be pretty easy to check if Cache was true, all we’d have to do is look at the right-most bit of the uint and check if it was 1 or 0

(true or false). Likewise for Reset, we’d look at the second bit, from the right. Debug, the third bit… and so on.

Let’s look at some examples to drive the point home:

00000001->Cache == true00000010->Reset == true00000011->Cache == true && Reset == true

So how do we express these states in actual Go code? We know how to do it in the struct approach:

config := Config{

Cache = true // Turn cache on

Reset = true // And reset

}

But what about now using these numbers to encode our state? 🤔

Enter bitwise operators!

// New blank config, uses the zero value for Config

// which is actually just a uint, so 0 or 00000000 in binary

var config Config

// Set Cache = true using bitwise OR (|)

// config is now 00000001

config = config | Cache

// Set Reset = true using OR again

// config is now 00000011

config = config | Reset

// Undo Reset using bitclear (AND NOT)

// config is now 00000001 again

config = config &^ Reset

// Check if cache is true

if config&Cache != 0 {

// Yes it is!

}

You can see there’s a 1:1 mapping between the struct/bool variant, and our uint variant. We can do all the same operations with our toggles:

- Combine them to form a group of settings (using bitwise OR

|) - Turn them off (using bitwise AND NOT

&^) - Check if one of them is set (using bitwise AND

&)

Why?#

So why do it like this? Isn’t the struct of bools clearer?

In a word… performance.

- The space required to store

nbooleans is nownbits rather thann * 8in the struct layout. This can add up! - Modern computers are really fast at doing bitwise operations like this… like really fast

- The constants are just baked into your compiled program, so no memory allocation needed

- This pattern often results in better CPU cache locality than large structs, the entire

uintcan fit into a cache line most of the time

I also think it’s quite a nice pattern once you get used to it and have seen it in the wild a few times, being able to compose settings at compile time is very useful. You can even wrap the bitwise operator stuff in functions and methods to present a nicer API.

Recap#

We’ve now answered all of our questions from the top of the post! Hopefully this makes a bit more sense but let’s have a quick recap before seeing a real example:

- Integers of increasing powers of two produce binary representations that differ by a single bit, the position of which moves left with each power of two

- The Go

iotamechanism provides a nice way of generating such integers at compile time and giving them useful names - By thinking of integers as this string of bits, we can efficiently store boolean information like configuration or state

- Bitwise operators can act on this representation and tell us which bits (settings) are set, and otherwise manipulate them

- Modern computers can do this very quickly and the data structure lends itself to high performance due to its small size and efficient operations

A Real Example: Hue#

Let’s try and drive this home with an example from a real codebase.

I recently wrote hue, an ANSI terminal colour library for Go, it leverages all the patterns we’ve discussed above to be stupidly simple to use and significantly

faster than most of the alternatives.

ANSI Colours#

Before we look at bitflags, let’s discuss ANSI colours briefly.

Terminal emulators (like iTerm2, terminal.app, ghostty etc.) do lots of weird and wonderful things to show us our command lines, one of which is interpreting ANSI Escape Codes in order to show coloured text

These codes work like this:

- Send the escape character

\x1b - Then a style code e.g.

[32. Different colours and styles have different numbers - Then

mto mark the end of the start sequence - Now print your string

- Then close the style with

\x1b[0m, the “reset” code

# Print "Hello" in green (32)

echo "\x1b[32mHello\x1b[0m"

Each style has a different number associated to it, and you can combine arbitrary numbers together to compose a new style.

Hopefully this is triggering alarm bells after reading this far!? Lots of numbers… each one a unique style… can compose together… 🕵🏻♂️

hue.Style#

In hue, these codes are a new type Style

type Style uint

And all the different supported styles are 1 << iota constants forming integers in increasing powers of two!

const (

Bold Style = 1 << iota

Dim

Italic

Underline

Reverse

Hidden

Strikethrough

Black

Red

Green

Yellow

// More below...

)

So styles can be composed as compile time constants using bitwise operators, just like we’ve seen above!

const style = hue.Bold | hue.Cyan | hue.Underline

Annoyingly the ANSI codes aren’t powers of two, so I turn these styles into ANSI Escape Codes using some of the stuff we’ve seen above. There’s a big switch statement that maps these Styles to their ANSI code, here’s a small snippet:

switch s { //nolint: exhaustive // We actually don't want this one to be exhaustive

case Bold:

return "1", nil

case Dim:

return "2", nil

case Italic:

return "3", nil

case Underline:

return "4", nil

case Reverse:

return "7", nil

case Hidden:

return "8", nil

case Strikethrough:

return "9", nil

// ... more

}

At the bottom of the switch I deal with combinations of styles (e.g. hue.Bold | hue.Underline) by:

- Iterating over the

Styles I’ve declared (in increasing powers of two) - Checking if the current style bit is set

- If so, include the associated ANSI code

var styles []string

for style := Bold; style <= BrightWhiteBackground; style <<= 1 {

// If the given style has this style bit set, add its code to the string

if s&style != 0 {

code, err := style.Code()

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

styles = append(styles, code)

}

}

return strings.Join(styles, ";"), nil

And that’s it!

See Also#

There’s loads more you can do with this pattern. Some useful resources to take a look at if this interests you: